|

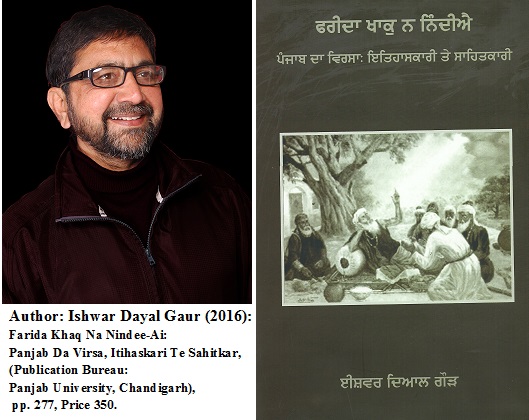

Farida Khaq Na Nindee-Ai:

Panjab Da Virsa, Itihaskari Te Sahitkar

|

|

Farida Khaq Na Nindee-Ai:

Panjab Da Virsa, Itihaskari Te Sahitkar

The book under review is a valuable contribution to the fast growing scholarly domain of medieval historiography of Punjab. What makes this study unique and engaging is its being grounded in the folk of medieval Punjab meticulously preserved in the rich treasure of the poetry of Punjabi Sufis, Gurus, and Bhagats. Medieval Punjabi poetry, a seamless blend of devout and erotic idioms, provides a solid aesthetic and poetic backgrounder to the often neglected field of Punjabi folk history and historiography. The medieval Punjabi poetry rooted in the syncretic communal character of the medieval Punjab taught the lesson of the unity of Being and His khalquat (human beings) and warned against all sorts of divisions in the name of religion, caste and creed. The medieval Punjab revered its poets and Sants on equal footing. Its glimpse cannot be obtained from the peer reviewed mainstream historical research based on research material of official data-bank. The mainstream history and historiography represents the people of Punjab through different colours of religious glasses. It simply tells us the structured ‘history of the poetry’. But it fails to reveal the ‘poetics of History’. The socio-cultural space of Punjab (Punjabi-tiranjan), informed the author, is beyond the reach of the mainstream medieval Punjabi historiography.

The learned author weaves an engaging and challenging counter narrative of medieval Punjabi history while delving deep into the rich and until now unexplored vast domain of Punjabi folk, culture and literary world of the unlettered. To come closer to the natural milieu of medieval Punjabi world of folk life and vision, Ishwar Dayal Gaur chiselled new paradigms of “Farid-Nanak Kaida”, (primer of Farid and Nanak), “Satjugi Darwar” (Kingdom of Spiritual world), and “Tiranjan of Eman” (socio-cultural space of faith). It is through the iconoclastic barrels of such paradigms that the author enabled the marginalised voices to once again stand up and speak for themselves. It opened the doors of the closed cellars of the medieval poets, pirs, murshids and qissakars (story-tellers) to speak for themselves. The author tells us that folk is alive and it has its own genealogy. Any history that disconnected itself, cautioned the author, from its own folk genealogy becomes dry and oppressive.

Gaur further writes that “Farid-Nanak Kaida”/“Satjugi Darwar” reminds us that Punjabi society owes its evolution to an interfaith dialogue among divergent faiths, religions and social movements occurring at the single folk time zone which is far more complex to be decoded by the linearly tailored and modernity oriented paradigms of historiography based on the methodologically sound mainstream history. Farid-Nanak paradigm introduced an alternative way to explore medieval Punjab buried under the debris of one-sided historical facts well preserved in the State guarded official archives. It gives, the author emphasised, more space and value to the folk memory judiciously kept alive in the ‘universal’ memory of the syncretic community’s cerebral space. It is such a folk paradigm, argued the author, which gathers the required strength to make a rupture in the mainstream hollow historiography. The mainstream historiography did not provide any space to folk literature and often presents the later as non-intellectual thing. The people history and folk archives, asserts the author, need to be brought into the pages of factual history.

Ishwar Dayal Gaur emphasizes that the Punjab cultural matrix (socio-cultural space) is a soothing concoction of divergent social, religious, cultural and linguistic signifiers, creations and artefacts laced with syncretic folk musk. It is much more ancient than ancient limits of the mainstream historiography. It has no affinity with those discourses, narratives, stories, ideologies, practices and idioms that foment enmity between clans and faiths, and construct counter hegemonies of varied varieties. It considers Khaq or mitti (one’s primordial cultural space/vernacular cultural space) as pious and native where folk memory digitised in the Kalams (poetic narratives) of sufis, qissakars and pirs sets the rules of social and individual interaction devoid of caste and religion. Baba Farid and Baba Nanak assign utmost importance to the primordial cultural space of people. The author has referred to many couplets of the spiritual poetry of Baba Farid and Baba Nanak in order to highlight the importance of folk history and its contributions towards the evolution of syncretic Punjabi socio-cultural space. He further stated that the new paradigm of Farid-Nanak Kaida teaches the art of making a distinction between the ‘history of literature and culture’ and ‘literature and culture of history’.

The learned author made a logical distinction between the ‘history of literature and culture’ and ‘literature and culture of history’. The ‘history of literature and culture’, argued the author, thrives on the factual database accumulated in the official archives of the State. But the ‘literature and culture of history’ has nothing to do with the dominating and hegemonising sermons of the mainstream historiography. It owes its evolution to fertile land of Punjabi-tiranjan. The mainstream literary historiography, according to the author, presents a distorted picture of the medieval Punjab while pigeonholing it into mutually contradictory faiths/religions. Whereas the ‘literature and culture of history’ provides a holistic perspective wherein socio-culturally diverse space of Punjabi society can be seen naturally interacting among itself. Dialogue and continuous interaction between various view-points, meticulously narrated in the folk literary world of medieval Punjab, made it totally different from the one (mutually repulsive) as projected in its mainstream history. The major difference between people history and mainstream archival history is that the former talks about the syncretic tradition of socio-cultural ethos of Punjabi society whereas the later tells us only about its divisive discursive logic. The former lives in the memory of people and folk-literature. The later is kept alive by the hegemonic dictates’ of the elite/State. The author opined that ideologues of those movements/ideologies who discarded/forgotten the paradigm of socio-cultural faith as taught by Baba Farid and Baba Nanak are either already vanished away from the land of Punjab or are on the brink of the extinction or got absorbed by the mainstream.

In a nutshell, the author has carved a brilliant counter-narrative that forces the reader to think afresh and at the same time to doubt what s/he learnt from the silky pages of the official texts. This bold and engaging study will give rise to a new thinking and debate about the urgent need of relooking at medieval Punjab through the eyes of its pirs, poets, qissakars and gurus and to find new ways to encounter the complex challenges faced by the contemporary Punjab. I congratulate the author for penning this brilliant text, which would be appreciated widely by the admirers of Punjabi cultural heritage and the students of medieval historiography of Punjab.

Posted on www.ambedkartimes.com december 21, 2016 |

|

DR. RONKI RAM’s MOTHER PASSED AWAY |

|

It is to inform with great heart and grief that Honorable Dr. Ronki Ram’s mother Smt. Shanti Devi passed away peacefully amidst her children, grand and great- grandchildren in her village Sahri, Tehsil & District Hoshiarpur on November 12, 2016. She was born and brought up at Lyallpur (now in Pakistan). She migrated to her native village Kalewal Bhagatan near Mahilpur during the partition in 1947 and married in the same year with Sh. Harmesh Lal of village Sahri (Hoshiarpur).

Smt. Shanti Devi was very religious lady, herself a matriculate, she was the main motivating force behind Dr. Sahib Professor Ronki Ram's higher education and his consistent academic contribution towards the various issues of Dalit writings over the last two and half decades.

www.ambedkartimes.com pays its deep condolences to the bereaved family and prays for the peace of the departed soul.

For more information, please contact Dr. Sahib.

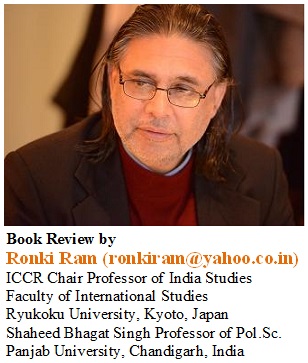

Dr. Ronki Ram

ICCR Chair Visiting Professor of India Studies

Faculty of International Studies

Ryukoku University

Kyoto, Japan

WhatsApp +91-9779142308

E-mail: ronkiram@yahoo.co.in

Dean, Faculty of Arts

Honorary Director, ICSSR, North-Western Regional Centre

Shaheed Bhagat Singh Professor of Political Science

Arts Block IV, Panjab University

Chandigarh 160 014 (India)

Mob: 0091-9779142308

E-mail: ronkiram@yahoo.co.in

Prem K. Chumber

Editor-in-Chief: www.ambedkartimes.com

Posted on November 13, 2016

Dear Dr. Ronki Ram Ji,

I have just read the sad news of your mother’s passing away. It is really a great loss to the family. Mothers play a very special part in our lives and stay in a very special part of our hearts. The loss of a mother creates a void that cannot be filled. My deepest sympathy and condolences to you and your family.

Regards,

Arun Kumar (UK)

Posted on November 13, 2016 |

"IDEAS OF ‘FREEDOM’ IN THE FREEDOM MOVEMENT OF INDIA” |

|

Photo Caption- Honorary Director, ICSSR North-Western Regional Centre and Dean, Faculty of Arts,

Panjab University (PU), Prof Ronki Ram addressing the prestigious PU Colloquium on the topic of “Ideas of

‘Freedom’ in the Freedom Movement of India” at the Dr. SS Bhatnagar Auditorium, PU Campus on February 25. |

Chandigarh (Ambedkar Times News Bureau): “The promotion of English language and dissemination of knowledge gave rise to renaissance in India – the cradle of ideas of freedom”, said Honorary Director, ICSSR North-Western Regional Centre and Dean, Faculty of Arts, Panjab University (PU), Prof (Dr.) Ronki Ram in his talk at the prestigious PU Colloquium in PU Campus here on February 25, 2014.

Prof Ronki Ram was speaking on the topic of “Ideas of ‘Freedom’ in the Freedom Movement of India” at the Dr. SS Bhatnagar Auditorium. PU Vice Chancellor Prof Arun Kumar Grover presided over the Colloquium.

Prof Ronki Ram said that the English had decided not to repeat the blunder that snatched the reins of rule from them in the continent of America. Thus in the beginning they refrained from introducing English education in India lest it encourage growth of nationalism among Indians. It was the reason that they followed the policy of promoting indigenous system of education. He mentioned that the East India Company founded Calcutta Madrassah in 1781 to encourage education in Persian & Arabic literature, and Banaras Sanskrit College in 1791 to promote Sanskrit learning. English education was imparted, somehow, by private individuals and missionaries, he added.

Prof Ronki Ram said that the Renaissance in India probably coincided with the social activism of Raja Ram Mohan Roy. The enchanting journey on the terrain of floating ideas of freedom began by Raja Ram Mohan Roy was taken further by the concerted efforts of Debendranath Tagore, Keshavchandra Sen, Iswarchandra Vidyasagar, Michael Madhusudhan Dutt, Paramahamsa Ramakrishna, Swami Vivekananda, Bhawani Charan Banerji, Rewachand Gyanchand, Rabindranath Tagore, Aurobindo Ghosh, Mahatma Gandhi and Dr. B. R. Ambedkar.Though some how they differed in their perspective about the freedom, he further added.

Prof Ronki Ram said that for Tagore, the freedom was spiritual. Gandhi Ji believed that India could achieve freedom as swaraj only through acceptance of considerable personal and political obligation. Large number of PU fellows, teachers, researchers and students participated in the colloquium. |

|

|